How to weigh up an executive pay scheme

Good management can make a huge difference to a company's fortunes and make its shareholders richer. Bad management can do exactly the opposite.

When you are thinking about investing in a company it's a good idea to find out whether its management team are being incentivised to do the right things for its shareholders.

Too often executive pay plans can be summed up as heads they win, tails you lose.

That's because the targets that management need to meet to get their hands on large bonuses are often not based on achieving things that grow the value of a company. They can actually end up making shareholders worse off.

In this article I am going to look at the pros and cons of various measures of company performance that are used in executive pay plans. I'll also give you some pointers on how you can work out if a company's management team are acting in your best interests.

Phil Oakley's debut book - out now!

Phil shares his investment approach in his new book How to Pick Quality Shares. If you've enjoyed his weekly articles, newsletters and Step-by-Step Guide to Stock Analysis, this book is for you.

Share this article with your friends and colleagues:

The curse of earnings per share (EPS)

EPS is probably the worst measure of company performance out there. Yet companies, the financial media and many investors remain obsessed with it. It may be simple to understand - the profits available to each share - but it has been abused for far too long.

Sadly for investors, EPS growth is at the heart of most management incentive plans. Some of the targets set for some managements are laughably easy such as increasing EPS by more than inflation when there isn't any meaningful inflation to speak of.

There is nothing wrong with EPS growth if it comes from selling more stuff profitably using a company's existing assets. However, in a world where borrowing money has been very cheap (due to low interest rates) for a long time now, it has become very easy for management teams to grow EPS by spending more money.

As long as a company invests in a project that earns more money than the interest on the borrowed money to finance it, EPS will go up. This does not mean that the project will earn enough money (by this I mean a high enough interest rate) for shareholders to compensate them for the risks they take by being the last in the queue to get paid.

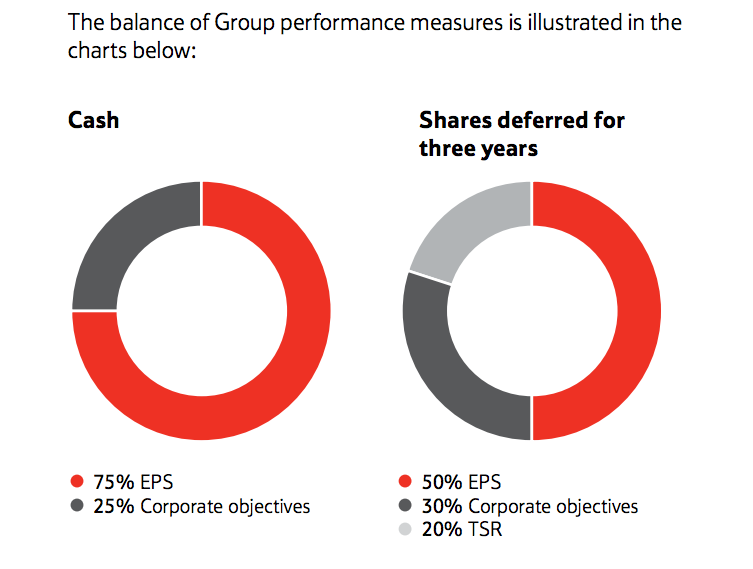

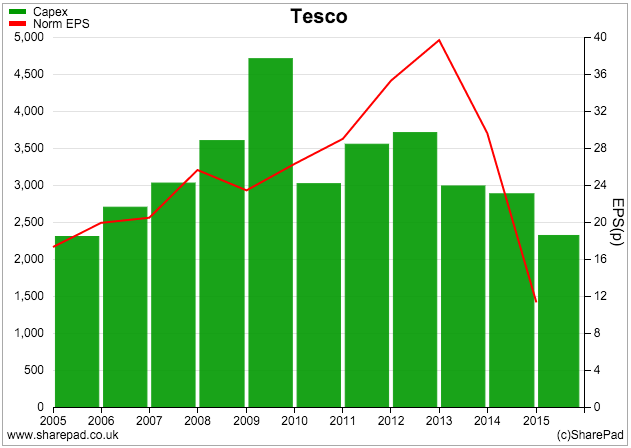

One of the best recent examples of this in practice is Tesco. You'll find the details of a company's management incentive plan in the remuneration report of its annual accounts. Below is a snapshot from Tesco's 2011 accounts before the company came a cropper.

75% of the cash bonus was linked to growth in EPS. This was at a time when Tesco was spending heavily opening supermarkets all over the world - something which was proven to be a very bad long-term investment when profits collapsed in 2014. But as EPS was going up the management weren't complaining as they were cashing their bonus cheques.

The other main abuse of EPS has been the increasing use of share buybacks by companies in recent years. Managements have been able to pay very high prices for their company's shares - often a lot more than they are worth - but still increase EPS and thus their bonus payments. This is because the buyback is funded from retained profits or borrowing. This reduces profits by increasing interest payments or reducing the interest received on the cash balance. If the percentage fall in profits is less than the percentage fall in the number of shares in issue, EPS will increase.

Buying overvalued shares actually destroys value for shareholders even if EPS goes up. (To read more on why this is, click here). You can work out for yourself whether a share buyback is good for you by using the share buyback tool in SharePad.

Return on capital employed (ROCE) is a much better measure

There are some drawbacks with most measures of company performance, but ROCE is probably the best of the bunch. That's because it measures what a company is getting back in profits as a percentage of all the money it has invested in the business. This is the main weakness of EPS.

Generally speaking an increasing ROCE is a sign that a company is improving and becoming more valuable. That said, ROCE can still be abused by company managements.

For example, it can cut investment and boost profits and ROCE by operating with old, worn out assets. Profits increase as assets become written off and have no depreciation expense which also reduces capital employed at the same time. You can check for this by comparing the capex to depreciation ratio for a company. If it is declining and falling below 1 times this may be a sign that a company is under-investing.

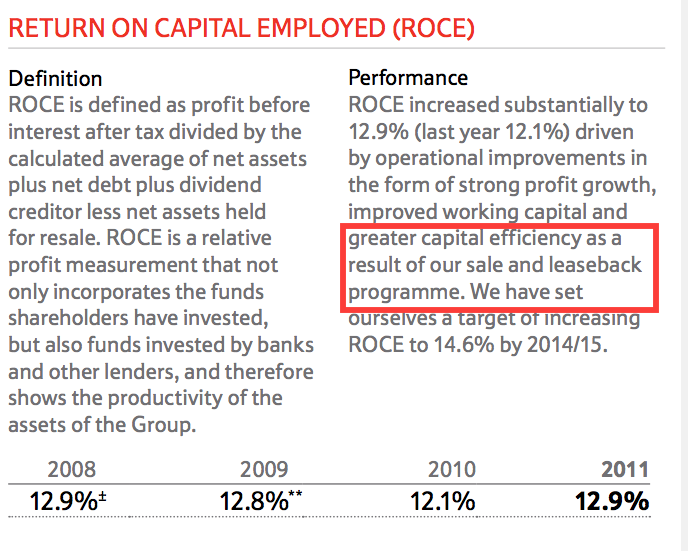

More companies are adopting ROCE targets for their management teams. However, you need to look at how they are defining ROCE. Here's Tesco's definition from its 2011 accounts:

Tesco's definition of ROCE excluded its pension fund deficit which is a long-term debt-like liability. It also excluded all the supermarkets that it had sold to and rented back from property companies and then told shareholders how this had boosted ROCE. Rented, off-balance sheet assets should be included if you are to have a reliable measure of ROCE. Tesco's ROCE was significantly less if measured properly but very few shareholders complained about the fact that management bonuses were being paid on this inaccurate measure.

SharePad's ROCE calculations include pension fund deficits and also give you an option of adjusting the calculation for rented, off balance sheet assets with a lease-adjusted version. (click here to read more about this topic).

Free cash flow

I am big fan of free cash flow but like ROCE it has to be calculated properly so that it is meaningful and not abused. Ideally it should do the following:

- Not penalise investing for growth (higher spending on new assets and the build up of stock - both of which reduce free cash flow).

- Be based on an accurate estimate of maintenance or stay-in-business capex.

- Be based on cumulative free cash flow over a number of years so that it is less prone to short-term manipulation.

I've written an article on how you can analyse free cash flow in more detail (click here to read).

Total shareholder return (TSR)

TSR (the change in share price plus any dividends received) is a common part of management pay plans. I am not a fan of this.

Investors should focus on total returns but I am against company directors being paid extra for them for a number of reasons. First of all, if management do their jobs well and increase ROCE - and get paid for that - then the share price will look after itself. They don't need to be paid twice.

TSR can also go up if stock markets are frothy and shares become overvalued. This has nothing to do with the actions of management. This is why you'll often see TSR dropped from plans when the stock market is falling or the company is struggling.

Despite my dislike for EPS, it does seem to drive short-term share prices. If a management pay plan is based on EPS and TSR then, by boosting EPS, they can get paid twice for the wrong reasons.

The other issue to consider is dividends which are entirely at the discretion of the management and a key part of TSR. A management team could boost TSR for a year by borrowing money and paying a large special dividend. But the borrowing could stretch the company's finances and increase the risk for shareholders. Why should management get paid for that?

TSR should not include the cash spent on share buybacks. This is a use of company retained profits to buy back shares - and often destroys rather than enhances shareholder value. Buybacks are often referred to as cash returns to shareholders and some companies include this in their definition of TSR. All that is really happening is that some - not all - shareholders are given the opportunity to sell their shares back to the company.

This is something that they could have done anyway by selling their shares through a stockbroker. Unless a share buyback leads to a higher share price or a bigger dividend it is not a return to shareholders.

Yet if a company calculates TSR including the cash return from buybacks then management can get paid for doing them. They will get extra pay on top if the buyback increases EPS as well.

Do management eat their own cooking?

As well as looking at management pay plans you should pay close attention to how many shares that they own. I want to own shares in companies where the management have a meaningful amount of money invested as well. This incentivises them to act in their and your best interests.

Compare the value of their shareholdings with their basic salaries (you can find this information in the remuneration section of the annual report). Anything less than two times annual salary would be seen as poor. It is surprisingly common for this to be the case.

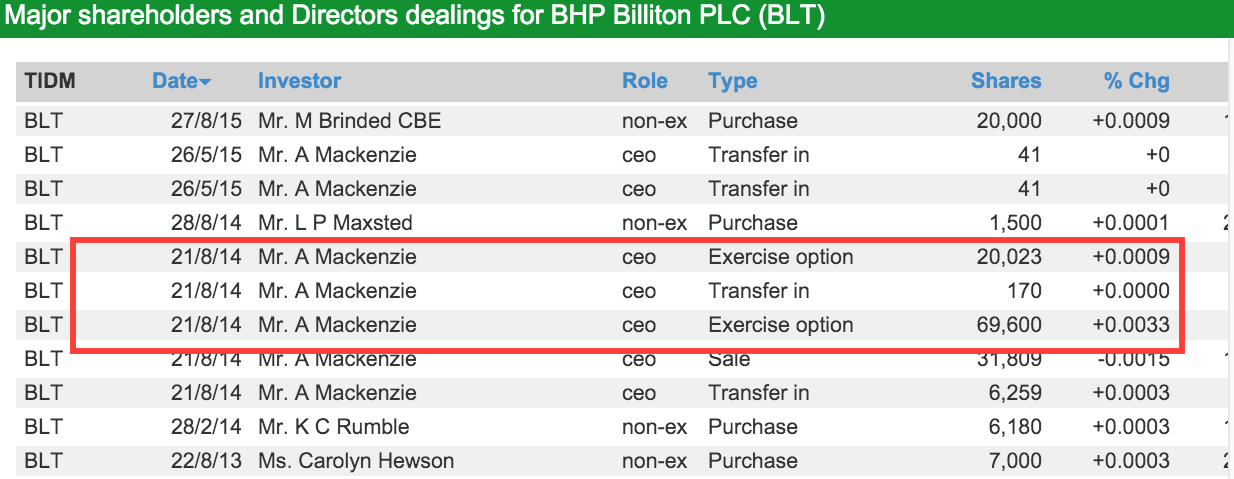

Also look to see if management are buying shares with their own money. I've known company directors to build up shareholdings in companies entirely due to bonus awards of shares or exercising share options. This is not the same or as meaningful as putting their hands in their pockets and spending their own cash. You can check how directors are buying shares in the directors' dealings tab in SharePad.

To sum up

- Be wary of management pay plans that are overly dependent on EPS

- Check that the performance targets are not too easy

- Look for companies where the management is incentivised to increase ROCE and where ROCE is calculated properly.

- Look for directors to own a meaningful number of shares in the company - at least twice their annual salary.

- Make sure that directors are mainly buying shares with their own money.

If you have found this article of interest, please feel free to share it with your friends and colleagues:

We welcome suggestions for future articles - please email me at analysis@sharescope.co.uk. You can also follow me on Twitter @PhilJOakley. If you'd like to know when a new article or chapter for the Step-by-Step Guide is published, send us your email address using the form at the top of the page. You don't need to be a subscriber.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.